Previous Page

${prev-page}

Next Page

${next-page}

ID Physician FTE

ID Physician FTE

B. DEFINITION OF AN FTE

1. Measuring Effort

For each component of an FTE, there is an associated common methodology used by hospital administration and/or department leadership to measure the work effort associated with individual components.

Clinical: Total patient-facing hours, days on inpatient services, on-call shifts, or time spent at half-day clinics and administrative effort (i.e., documentation) associated with patient-facing time.

Administrative: Total hours spent relative to the role (sometimes formally tracked via a time sheet).

Research: Total hours working on current research activities or applying for grant opportunities.

Teaching: Total hours associated with didactic teaching (e.g., planning lessons, grading assignments, teaching courses).

Strategic: Total hours spent performing activities related to a strategic obligation (i.e., meeting attendance) and other tasks directly associated with a short-term strategic initiative.

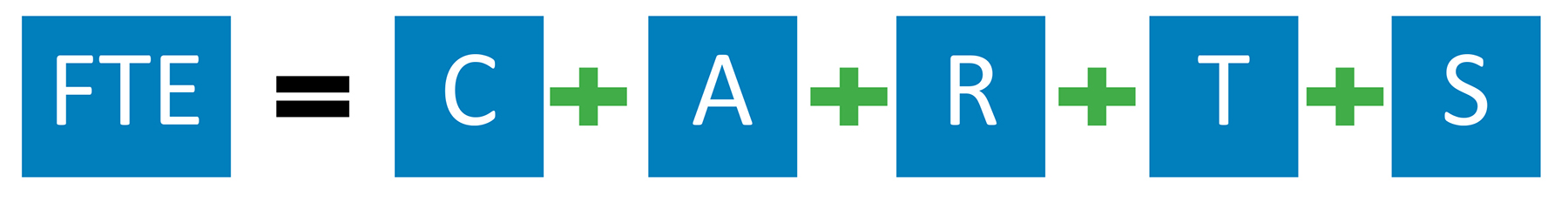

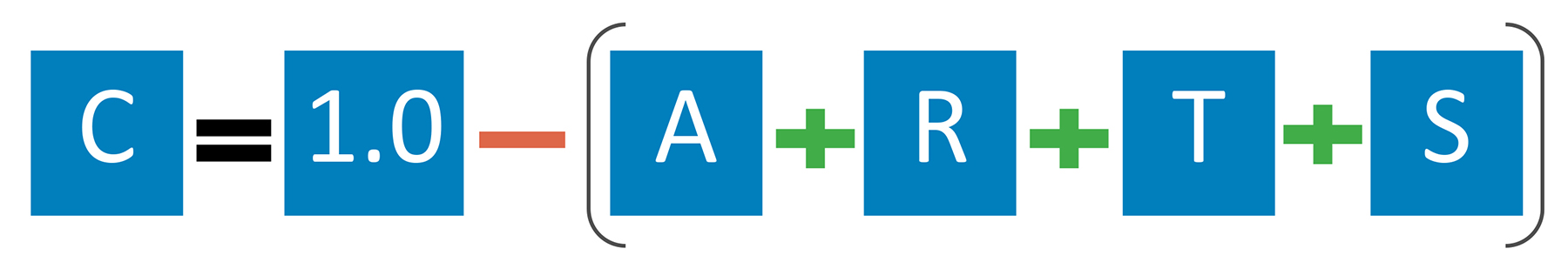

Commonly, physicians’ clinical effort, regardless of employer, can be understated compared to their actual contributions. This is often due to a mistaken assumption or perception that clinical effort is simply the remainder of 1.0 FTE less all nonclinical responsibilities. In reality, each component of effort should be calculated independently and not confined to a ceiling of 1.0 FTE in total. See figures 1 and 2 for the recommended and imprecise ways to define an FTE.

FIGURE 1: The Recommended Way to Define an FTE

FIGURE 2: The Imprecise Way to Define an FTE

How effort is measured can vary by practice setting and employer, and most physicians are not deployed in every category defined in this section. While employers — academic and nonacademic — may not measure effort in the same way, they do all have baseline expectations of full-time employment. See section II.D for a detailed case study of why it is important for these baseline expectations to be formally defined so changing effort can be appropriately recognized.

FTE Considerations for Health System-Employed Physicians

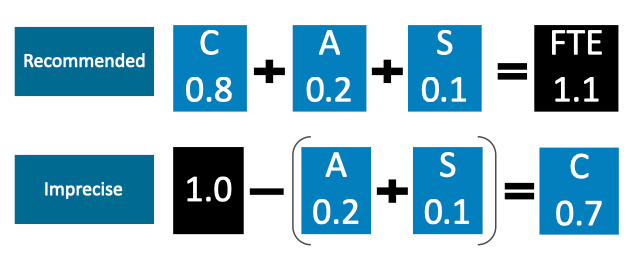

For physicians employed with a health system, the most commonly recognized FTE components include clinical, administrative and strategic efforts. For example, Jane Doe, MD, who is employed by a health system as a medical director (defined as a 0.2 administrative FTE), has been asked to participate in a year-long EHR transition initiative (defined as a 0.1 strategic FTE), but her clinical responsibilities remain the same as before the strategic role was added (defined as a 0.8 clinical FTE). See figure 3 for how the recommended and imprecise way to define an FTE impacts the perception of Dr. Doe’s total contributions.

FIGURE 3: Example FTE Buildup for a Physician Employed at a Health System

FTE Considerations for Physicians in AMCs

For physicians employed or affiliated with an AMC, it is more common for them to have research and teaching components of effort. As an example, Jane Doe, MD, is a medical director of antimicrobial stewardship (defined as a 0.2 administrative FTE), teaches courses at the medical school in a nonclinical setting (a 0.1 teaching FTE), participates in grant-funded reasearch (a 0.1 research FTE) and works the equivalent of a 0.7 FTE in the hospital and clinics. See figure 4 for how the recommended and imprecise way to define an FTE impacts the perception of Dr. Doe’s total contributions.

FIGURE 4: Example FTE Buildup for a Physician Employed at an AMC

FTE Considerations for Private Practice

In contrast to physicians employed by academic or nonacademic institutions, private practice physicians tend to be paid on a revenue less expense model such that individual FTEs and the calculations of them are less important. However, many private practice physicians are contracted by hospitals for services — clinical and nonclinical — so defining baseline expectations is vital. These baseline expectations can then be defined in FTE terms.

For example, Jane Doe, MD, is a private practitioner and is contracted to be medical director of infection prevention at a local hospital. Time expectations are not defined, but she is told that her salary equates to 10% of the salary a full-time ID physician would have at the organization. Because Dr. Doe is familiar with the concept of FTEs, she infers that the job is assumed to require 200 hours annually (a 0.1 administrative FTE within that organization). With this familiarity and understanding, Dr. Doe is more equipped to advocate for higher compensation if the job requires more effort than initially anticipated.

2. Standardization

As ID physicians work to standardize how effort is defined within their organizations, employment expectations should be defined based on the measures of time appropriate for each component of effort. As an example, the clinical portion of a physician’s effort (clinical FTE) should (1) be based on a standard definition, (2) be applied to all ID physicians in a department, division or group, and (3) detail all required clinical activities, including in-house and beeper calls. This standard definition allows an employer or employee to assess when actual work effort varies from what is expected. Below are example work expectations for clinical effort for academic and nonacademic settings when a physician is at 100% clinical effort (i.e., 1.0 CFTE). (To be certain, the definition of a full-time clinician or 1.0 CFTE may not be the same at every organization.)

• A defined number of weeks that are worked per year in a specific patient-facing setting (outpatient, consult weeks, etc.).

• A defined number of shifts per year for each type of shift provided (i.e., inpatient service, restricted call (defined as time the physician is required to be on site in the hospital), backup call).

• A defined number of half-day clinics per week.

◦ Sample standard for a 1.0 CFTE: 48 weeks per year.

◦ Sample standard for a 1.0 CFTE: 73 24‐hour restricted/in-house call shifts per year.

◦ Sample standard for a 1.0 CFTE in nonacademic settings: nine half-day clinics per week and one remaining half-day reserved for clinical documentation.

◦ Sample standard for a 1.0 CFTE in some academic settings: eight half-day clinics per week and two remaining half-days reserved for clinical documentation and other non-patient-facing efforts.

• Attendance at a minimum number of department or professional staff meetings, or additionally for academic settings, attendance at a minimum number of education meetings (e.g., grand rounds, journal club).

• Completion of a chart within a defined number of hours or days after a patient encounter.

Attendance at department or professional staff meetings, the time it takes to complete charts, and interviewing candidates for physician or faculty positions or fellowship/residency programs are typically considered part of the job and not formally tracked but do take a significant amount of time. For this reason, to the extent physicians can track this time, understanding deviations from what is typical becomes much simpler and can inform compensation negotiations with administrators. Physicians who do track this time report using computer software and/or smartphone applications.

3. Purpose

With an FTE clearly defined and established, physicians and employers can collaborate more effectively to allocate physician resources to align with the organization’s goals. Without these minimum expectations established, however, physicians’ CFTEs are often understated compared to actual clinical effort. Section II.D shows a basic example of how a resourcing decision was made easier and more accurate after FTEs were clearly defined.